This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Contemporary and Future Operations

Reuters/Suhaib Salem/RTXT3U9

Masked Palestinian militants, some from Hamas, arrive at a news conference in Gaza City, 6 October 2010.

Slaying the Dragon: The Future Security Environment & Limitations of Industrial Age Security

by Shaye K. Friesen and Andrew N. Gale

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Introduction

When it comes to designing practical force protection measures, defence planners need to be prepared for an international security environment that is increasingly characterized by uncertainty, volatility, complexity, and rapid change. In this environment, defence planners cannot simply continue to rely upon linear planning or traditional protection techniques of the industrial age as the sole antidote to future multi-directional challenges. With such a chaotic and unpredictable security environment, there is a need to redefine and replace old approaches with a new network-age model in the application of security risk management; hence the need to ‘slay the dragon’ of our past. Through an examination of the future security environment and an analysis of the limitations of current industrial-age approaches, this article will highlight the requirement, key characteristics, and implications of a new network-age approach for security and force protection techniques that are matched to the needs of future forces.

Strategic Context

The forces of globalization are affecting the political, military, and economic world order in new, unpredictable, and potentially destabilizing ways. Patterns of conflict and their resolution will not unfold as traditionally characterized by peace, conflict, and post-conflict reconstruction activities. In certain regions of the world, failed and failing states will permeate the security landscape in our lifetime, and create the conditions for complete societal collapse. Failed states will spawn violent secessionist movements, civil and regional wars, famine, disease, and criminal predation, all of which will have spillover effects.1 Transnational threats, such as non-state actors, international crime syndicates, tribal, religious, and ethnic extremism and

terrorism will increasingly form new sources of instability that will challenge national interests asymmetrically.2 Fuelled by radicalism and extremism, increasing competition for resources, climate change, and demographic changes, future conflict will likely be violent, protracted, and messy. The burgeoning population growth in major urban centres, particularly in areas of the developing world, will have implications for both public and private operations, as well as disruptive effects on the supporting capacity of the global economy and environment.3 Global competition for natural resources and environmental scarcity will trigger humanitarian disasters and the mass migration of people and refugees. Climate change will intensify the build-up of energy shortages and create further environmental and resource scarcity, as well as competition for natural resources, increasing the likelihood of failed states and terrorism.4

The ongoing proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (WMD), especially into the hands of ‘rogue’ states or non-state actors, will be of particular concern. Such weapons will provide

non-state actors and small, radical organizations with the potential to orchestrate destructive and disruptive effects on an enormous scale. Non-state actors, who are being empowered by modern technology and weaponry, threaten to undermine the traditional strength and numerical superiority of military forces of organized nation states. These non-state actors intermingle and merge with a local population, apply non-traditional tactics, and can use our freedoms against more open societies.5 Indeed, the September 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States demonstrated that a handful of persons could undermine a nation’s security posture. The fear and impact generated by terrorist-initiated events involving chemical, biological, and radiological/nuclear (CBRN) materials has the potential to produce mass casualties and result in disproportionate impacts and unintended consequences that extend

far beyond the initially affected area.6 The potential for a catastrophic, state-threatening

defeat is implicit in the use of WMD. Rapidly spreading, global pandemics and infectious

disease have the potential to impact the population, infrastructure, and the economy on an enormous scale.7 Furthermore, the increase in interdependency of critical infrastructure, specifically within the key supporting sectors of finance, communications, and energy, will become a growing concern as vulnerabilities become exploited by cyber attack or brute force attack, resulting in disruption or denial of service and unimagined cascading consequences to the national well-being.8

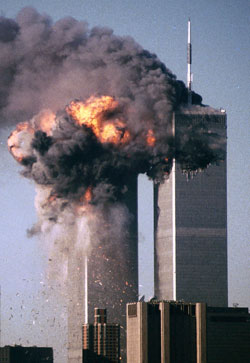

Reuters/Sean Adair/RTR2FZG

The twin towers of the World Trade Center, 11 September 2001, at the moment United Flight 175 crashes into the south tower.

Western nations may not have a ‘crystal ball’ to predict the future; however, understanding

the implications of the complex world of tomorrow, and predicting the threats that future will pose to the nation, is exactly what defence scientists and military operational planners are examining. Exploring the future security environment provides the necessary context and background information to ensure military forces can establish a coherent strategy and force structure for what lies ahead. Such analysis of the future security environment involves the shaping and thinking of military, government, and industrial planners, and, indeed, this knowledge is suggestive that a new method is required to address these current and future threats. Force planning scenarios can be developed allowing the extrapolation of probable capability requirements and the further development of a roadmap toward future investment

of limited and often completing resources in the out years. It is also a method that industrial security managers should become ready to address and discuss within their business communities. Current research has identified that Western nations will be challenged in addressing future strategic trends around the world, particularly in light of limited and competing fiscal realities faced by governments and industry. These trends include significant changes in globalization, migration, urbanization, climate,information, customization, and miniaturization of new technologies that translate into possible threats that have been collectively termed the ‘future security environment.’ While there may be differences in regards to the timing of when certain trends will occur, there is a general consensus among the strategic assessments from Western militaries, as well as in current academic circles, that the major security challenges facing tomorrow will include the following:9

- Geopolitics: continued globalization and interdependence of critical infrastructure; instability/conflict from discontent over political/economic disparities; the possible emergence of alliances or competitors that challenge the hegemony of the United States; potential for increasing fanaticism driven by failure of governance; enduring potential for state-on-state conflicts; expected increased demand for intervention in fragile and failed states (stabilization and reconstruction); ongoing concern regarding terrorism, criminal activity, and drug trafficking.

- Socio-economic: social instability in failed states; migration having a skilled labour

impact upon donor and recipient nations; declining ‘baby-boomer’ generation, reducing the local work force in Western nations; increase in migration and urbanization, population growth, especially within ‘mega cities;’ increase in displaced persons

resulting in food scarcity, poverty and conflict; more intra-state conflict and civil unrest, due to effects of migration and urbanization; urbanization leading to over-crowding and infectious disease outbreaks; pandemics spread by the relative ease of travel; uneven global economic growth. - Resource and environment: continued resource inequality leading to conflict over food, water, oil, metals, minerals; drought, and desertification in areas already having inadequate water supplies; demand for oil somewhat lessened by energy alternatives; competition for strategic metals and minerals; climate change impacting agricultural production and humanitarian crises; opening of Arctic waters; we will be reliant upon low-energy technologies, such as improved batteries and alternative energy sources.

In contrast, energy consumption and demand will soar in developing countries and increasingly urbanized zones. - Science and technology: nanotechnology developments will provide new miniaturized dual use technologies (for benefit or harm of society products), leading to smaller defence footprint; biotechnology will improve quality of life, create enhanced warriors, and result in new bio-weapons; advances in cognitive and behavioural science; increased reliance upon cyber technology for telecommunications to ensure functioning local finances in a competitive global economy; risk of potential for disruptive application of technology.

- Military: complex security environment (i.e., changing power structures, alliances, non-state actors, asymmetric threats); increased requirement for special operations, precision technology, and non-lethal weapons; changing methods of future warfare include cyber attacks, weaponization of space, proliferation of chemical/biological/

nuclear weapons in hands of non-state actors, and information operations.

Responsible planners and protection professionals, be they military, government, or industrial security managers, will need to look ahead at operating in a future security environment of highly complex, urban, and interconnected cyber elements, in which there will be no clearly delineated front lines that encapsulated the linear threats of the industrial age. It is

anticipated that future threat response will be undertaken in inhospitable environments, ranging from mountainous terrain to densely populated urban centres and congested littoral regions of the world, challenging the current institutional response agencies. Response to threats will inevitably require a simultaneous multi-dimensional approach that involves the various levels of government and industry in order to withstand the shocks, impacts, and stresses encountered by this future security environment.

No longer will the traditional method of protection and thinking work in this new emerging environment. Akin to knights of the 16th-17th Centuries in which the addition of armour was countered by more effective weapon systems (i.e., cross-bow, and, eventually, gunners),

which then saw a move to field fortifications to offset individual weaknesses, resulted in the reduced agility and precision of defending forces.10 For awhile, complex defensive fortifications protected troops and were able to guard strategic points through impregnable walls and barriers, but were susceptible to artillery bombardment and siege warfare.11 It can be argued that this analogy is repeating itself today, where modern defence forces and nations have increased protection and fortifications, only to be defeated by the agility and precision of opposing and often inferior opponents. In the evolution of warfare, protected armour has almost always resulted in a false sense of security against a swift and unpredictable threat. Recent operations in Iraq and Afghanistan have driven military units to become concentrated on large bases for force protection. Arguably, terrorists’ use of explosives and improvised explosive devices (IEDs) has created a false belief among security and force protection practitioners that an absolute ‘bubble’ of security can be provided in order to limit an adversary’s capacity to wage an asymmetric attack.

The reality is that vulnerabilities are everywhere and exist wherever one looks, and they translate into a form of siege warfare. While physical security and access control will remain

an important component in any future security plan, the security planner can no longer

consider such measures as a panacea toward the avoidance of the threats of the future. Indeed, a wide variety of future adversaries will exploit access to advanced technologies, control systems, and information technologies. These adversaries will operate autonomously, intermingle with the local population, and have at their disposal highly lethal anti-access capabilities (i.e., volumetric munitions and man-portable missiles and rockets).12 The intermingling of adversaries also provides the opportunity to influence attitudes, behaviours, and, thus, the allegiances of the local population and the reaction to events. The future will require people who have the requisite foresight and the ability to counter such vulnerabilities and gaps of asymmetry, which will include attention to the moral and cognitive effects of threat events upon employees and communities.

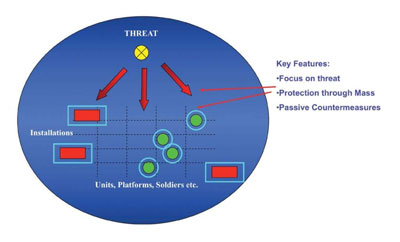

Industrial Age Security (threat based)

Limits of Industrial Age Security

Until the present, Western nations have addressed security issues through the tenets of the industrial age. Specifically, responses to threats have been primarily based upon the forecast

of an existing threat that has been termed a ‘threat assessment.’ Traditionally, threat assessment has tended to focus upon a small fraction of future conflict scenarios and environments. Often, if there was no perceivable threat, there was no response made by authorities to address the possible consequences of the threat being realized. A major drawback is that threat assessment is a reactive and linear process that is highly susceptible

to short-term distortions and changing perceptions of threat. Defence planners will need to look ahead at operating in the future security environment of highly complex, urban, and interconnected cyber elements, in which there will be no clearly delineated definition of “adversary” that encapsulated the linear threats of the past. In the future, far less emphasis will be placed upon assessing threat, and commanders will need to think of ways to adapt and respond to actions while concurrently minimizing risk and vulnerabilities.

Perimeter security measures tend to be passive in nature, and information firewalls are designed on access control and user permission monitoring. Field fortifications have almost always resulted in a false sense of security against a swift, agile, and unpredictable adversary. The strategy of building complex defensive fortifications imposes isolationist thinking that is neither sustainable nor compatible with globalization, the requirements of the local operating environment, or the emerging phenomenon of complexity science and complex adaptive systems.13 These symbiotic and sedentary fortifications have resulted in the creation of multiple ‘stovepiped’ systems that are vulnerable once intrusions occur. Perimeter security measures will not eliminate all vulnerabilities, and can no longer be considered as a panacea toward the avoidance of the threats of the future. Within an information-age approach, the

aim is to adopt a more proactive and anticipatory approach that exploits military, commercial, and civilian tools and networks to maximum advantage in order to leverage information faster than an adversary and facilitate redundancy.

In contrast, much effort has been made to minimize threats and safety concerns through a

form of hazard avoidance, which, in turn, limited or stagnated the ability to respond effectively and quickly in our emerging global integrated and networked society. Techniques designed

with the principle of hazard avoidance might be able to address conventional fighting

situations in open country warfare, but they are not designed to address the complexity of

local and non-state actors and the types of conflict environments in urban and littoral areas that will be encountered in the future security environment. The lack of visibility and situational awareness, difficulty in discerning the adversary and adversarial intent, environmental effects (i.e., rain, dust, buildings, etc.) will further constrain the effectiveness of hazard avoidance in future conflicts. These industrial age approaches to security are not optimized for the complex challenges of the future security environment, and they have resulted in a security system in which defensive systems have garnered the most resources with little requirement or incentive to proactively innovate or develop agile solutions. Organizations must be able to converge and adjust more fluidly the activities and expertise required for improved responses to emerging hazards. Future security systems must be more nimble and adaptive, so that they are capable of completely changing direction over the course of an operation to counter the widest possible hazard array.

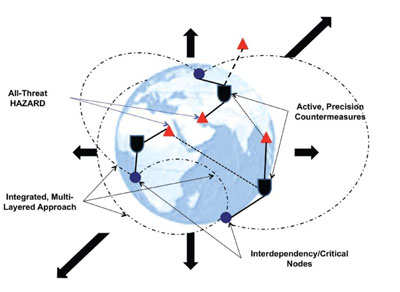

Towards an Information Age Force Protection Model

A new comprehensive approach to security management will be required that necessitates the incorporation of various agencies, non-state actors, multinational actors, corporations, and the public at large. Because all these entities will, in some form or another, be affected by a future threat event, a comprehensive approach framework will present interagency risks, including

the potential for more effective dissemination of information and awareness of possible misinformation. Central to this is a much broader and deeper requirement for information sharing, and a clear recognition of the linkages and capabilities among the various ‘players’ that will be part of the future protection network. The future security environment will demand solutions that are agile and adaptive.

One such approach consists of a model that is comprehensive, collaborative, cooperative, communicative, interoperable, and intelligent (C4I2). The adoption of a C4I2 model is about abandoning a narrow, limiting approach to security management by converting to a new way

of thinking about protection in terms of how we must address the multi-dimensional space of our future security environment. It is about transforming security and force protection capabilities to maximum effect through agility and adaptiveness to a highly integrated,

network enabled, and effects-based operating environment as envisioned for 2030.

Specifically, how we will coordinate and integrate with other levels, sectors, and security partners, how we capitalize upon multiple inter-dependencies of critical infrastructure, and

how we shield our rights, values, and society as we face these new threats will be paramount for our livelihood. For departments and agencies involved in implementing security solutions, the multi-directional integration of the following characteristics is required:

- Comprehensive– achieving a wide assessment of possible hazards and understanding

of mitigations strategies, which requires a larger networked approach among government and non-government organizations. - Collaborative– achieving integration of protection capabilities of security organizations and multi-national partners, such as government, military, academia, and various non-government organizations.

- Cooperative– achieving a coordinated working approach to the various threats of the future security environment, while respecting and adhering to the constitutional and human rights of citizens.

- Communication– achieving awareness and understanding that defines the linkages and capabilities of the mitigating agencies involved in the protective network. Today, the industrial age approach of ‘need to know’ must adjust to a ‘need to share’ among a highly integrated networked environment. Also, it becomes more imperative to communicate and advise citizens in a timely manner to ensure a greater cognitive understanding of the issues, and a reduction of community stressors.

- Interoperable– achieving in the future a seamless integration and interconnectivity of systems to allow the shielding ability of organizations to address threats and to achieve the required effects desired by society and industry. Further assessment is needed with respect to interdependencies required to achieve the desired supplementation to the abilities and agilities of industry and government, to protect them in today’s growing interoperable environment, which is increasingly becoming ever more interdependent with respect to the provision of critical services.

- Intelligent – achieving predictive and self-assessment tools that will have the ability to sense and direct response to hazards and the protection of critical systems. Intelligent supported analysis, which will rely upon automated sensing and data-fusion systems, will need to be customized to particular hazards and vulnerabilities. Properly exploited intelligent mechanisms will facilitate a convergence of physical, cyber, and cognitive protection capabilities in addressing the threats of the future.

By leveraging the benefits of a more comprehensive approach to security risk management, and by exploiting partnerships with other organizations engaged in the provision of security and intelligence activities, the end state will be a more capable, responsive, and stable protective environment. Such an environment will not only facilitate protection, but it will also provide a layered, in-depth and mutually re-enforcing system that is capable of absorbing the broadest range of threats. The implementation of methods and approaches that are

compatible with the C4I2 model will allow security practitioners to achieve a significantly more robust business continuity program because it will allow them to continue to function in the

face of sustaining critical losses or damage in certain areas.

Network-Age Shield (Vulnerability based on risk analysis)

In the emerging society of the network age, it will be imperative that security managers tie together physical, informational, and cognitive/social domains in addressing the myriad

possible security challenges. There will be a requirement to shift to vulnerability and risk-based analysis to manage all hazards, both human-induced and non-human related. It will be important to move away from a purely threat-based approach, whereby threats can either come or go, and focus upon the vulnerabilities of operations before addressing the possible threats to those operations in order to provide a realistic and cost-effective approach to one’s analysis. Just as Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) attempts to achieve an integrated security framework for a building,14 so too must we adopt an overall

information-age protection model that evolves to deal with the integration of the more complex relationships of local and national government, public, and industrial security teams and managers. In addition to the protection of tangible assets (i.e., personnel or facilities), the security of intangible assets such as belief systems, opinions, relationships, and interests is an area that is usually not well appreciated or understood by government officials, corporate executives, and security managers. Often, the protection of intangible assets is just as critical to the success (or failure) of operations. Subsequently, a new emphasis will be required with respect to leveraging information within an integrated, active, and layered approach, which

has developed into one concept termed Network-Age Shield. This future shield concept is intended to address the challenges of the future security environment by leveraging the realities and opportunities it will present. These include integrating the capabilities of other agencies and multi-national partners, closely synchronizing actions and orientation with decision makers from various levels of government, industry and the public, ensuring that

there is multiple and overlapping levels of redundancy in cyber communications and computer systems, investing in the next generation of artificial intelligenc and predictive tools, and customizing protection against particular hazards and vulnerabilities.

The shield concept, in addressing the future security environment, will likely lead to a number

of possible implications forgovernment and industry:

- Individualized training of personnel from the point of selection and throughout a period of employment career retention;

- Research and development into adaptive materials and embedded technologies, including new analytical tools and methods required to understand complex interdependent system vulnerabilities;

- A greater priority of rapid, if not continuous, organizational learning to improve infrastructure resilience;

- A sharing of resources between government, non-government actors, and industry to develop concepts and doctrine in order to develop systems of protection;

- A focus upon rapid information sharing, dissemination, and exploitation through changes in configuration of information technology systems; and

- A focus upon defensive “build-in” systems, capabilities and platforms of new equipment in use by governments, armed forces, and industry.

Conclusion

Current approaches to force protection and security management have been moderately successful in thwarting a generation of threats to a given organization’s assets. Assets that were protected in the past will still require a minimum level of protection in the future.

However, the use of industrial age security techniques alone will no longer be sufficient in addressing the new and complex risks arising in the future security environment. Traditional security practices will need to be supplemented by a more holistic understanding of the nature of future risks, and the adoption of increasingly agile, adaptive, and anticipatory protective measures. Elements that have not previously been considered or examined in detail will need to be addressed by security professionals. Given this situation, it is incumbent upon force protection professionals to recognize that they are part of the solution under a C4I2; approach that will work to mitigate the presence of current and emerging threats to our lifestyle and livelihoods. The broader defence and security communities are encouraged to investigate and discuss this proposed model to further address collective understanding and effectiveness toward learning and adapting professional practices in order to tailor responses to the asymmetric threats of the future.

![]()

Shaye K. Friesen is a Defence Scientist with Defence Research & Development Canada, Centre for Operational Research and Analysis (CORA). He is currently working in the Directorate of Future Security Analysis, Chief of Force Development.

Commander Andrew N. Gale, CPP, CFE, PCIP, currently a reservist, is recently retired from the Regular Force of the Canadian Forces Military Police, and, until his retirement, served as the Shield Domain Manager within the office of Chief of Force Development.

Notes

- Robert I Rotberg, “Failed States in a World of Terror” in Foreign Affairs (July/August 2002), pp. 130-132.

- Richard A. Matthew and George Shambaugh, “Sex, Drugs and Heavy Metal: Trans-national Threats and National Vulnerabilities,” in Security Dialogue, Vol. 29, No. 2 (1998), p. 163.

- United Nations, World Urbanization Prospect: The 2007 Revision (New York: United Nations, 2008), pp. 1-4.

- National Security and the Threat of Climate Change (CNA Corporation, Virginia, 2007), p. 16. Available at: http://securityandclimate.cna.org/report/National%20Security

%20and%20the%20Threat%20of%20Climate%20Change.pdf - United States, Defense Science Board Task Force, Force Protection in Urban. and Unconventional. Environments, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (March 2006), p. 4. Available at:

http://www.acq.osd.mil/dsb/reports/2006-03-Force_Protection_Final.pdf - Richard Danzig, Catastrophic Bioterrorism—What is to be Done? (Washington, DC: National Defense University, 2003), p. 2.

- nited States, Department of Homeland Security, National Population, Economic and Infrastructure Impacts of Pandemic Influenza with Strategic Recommendations (National Infrastructure Simulation and Analysis Center, 2007), p. 18.

- Steven M. Rinaldi, James P. Peerenboom and Terrence K. Kelly, “Identifying, Analyzing and Understanding Critical Infrastructure Interdependencies,” IEEE Control Systems (December 2001), p. 22. Available at: http://www.ce.cmu.edu/~hsm/im2004/readings/CII-Rinaldi.pdf

- Allied examples include: United Kingdom, Global Strategic Trends Programme 2007-2036 (London: Ministry of Defence Development, Concepts, and Doctrine Center, January 2007). Available at: http://www.dcdc-strategictrends.org.uk; United States, Department of Defense, The Joint Operating Environment 2008: Challenges and Implications for the Future Joint Force (Suffolk: United States Joint Forces Command, November 2008). Available at: http://www.jfcom.mil/newslink/storyarchive/2008/JOE2008.pdf

- Geoffrey Parker, The Military Revolution: Military Innovation and the Rise of the West, 1500-1800 (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1988), pp. 16-24.

- Ibid., pp. 12-14, 43.

- Frank Hoffman, “How Marines are Preparing for Hybrid Wars,” in Armed Forces Journal online version (March 2006). Available at: http://www.armedforcesjournal.com/2006/03/1813952/

- Edward A. Smith, Complexity, Networking and Effects-Based Approaches to Operations (Washington, DC: Command and Control Research Program, 2006); Dave Kilcullen, (Lt Col), Complex Warfighting (Canberra: Future Land Warfare Branch, 2004); Frank G. Hoffman, “Complex

Irregular Warfare: The Next Revolution in Military Affairs,” in Orbis (Summer 2006), pp. 395-411. - Randy Atlas, “Protecting Critical Infrastructure with CPTED,” presentation given to American Society for Industrial Security (ASIS), Emerging Security Trends and Solutions Conference, Las Vegas, NV: (19 May 2008).